Meta’s move into the open social web, also known as the fediverse, is puzzling. Does the Facebook owner see open protocols as the future? Will it embrace the fediverse only to shut it down, shifting people back to its proprietary platforms and decimating startups building in the space? Will it bring its advertising empire to the fediverse, where today clients like Mastodon and others remain ad-free?

One possible answer can be teased out of a conversation between two Meta employees working on Threads and Flipboard CEO Mike McCue, whose company joined the fediverse with its support of ActivityPub, the protocol that powers Mastodon and others.

On McCue’s “Flipboard Dot Social” podcast, he spoke to two leaders building the Threads experience, director of product management Rachel Lambert and software engineer Peter Cottle. McCue raised questions and concerns shared by others working on fediverse projects, including what Meta’s involvement means for this space, and whether Meta would eventually abandon Threads and the fediverse, leaving a destroyed ecosystem in its wake.

Lambert responded by pointing out that Meta has other open source efforts in the works, so “pulling the rug” on its fediverse work would come at a “very high cost” for the company, since it would be detrimental to Meta’s work trying to build trust with other open source communities.

For example, the company is releasing some of its work on large language models (LLMs) as open source products, like Llama.

In addition, she believes that Meta will be able to continue to build trust over time with those working in the fediverse by releasing features and hitting milestones, as it did recently with the launch of the new toggle that lets Threads users publish their posts to the wider fediverse, where they can be viewed on Mastodon and other apps.

But more importantly, McCue (and all of us) wanted to know: Why is Meta engaged with the fediverse to begin with?

Meta today has 3.24 billion people using its social apps daily, according to its Q1 2024 earnings. Does it really need a few million more?

Lambert answered this question indirectly by explaining the use case for Threads as a place to have public conversations in real time. She suggested that connecting to the fediverse would help users find a broader audience than those they could reach on Threads alone.

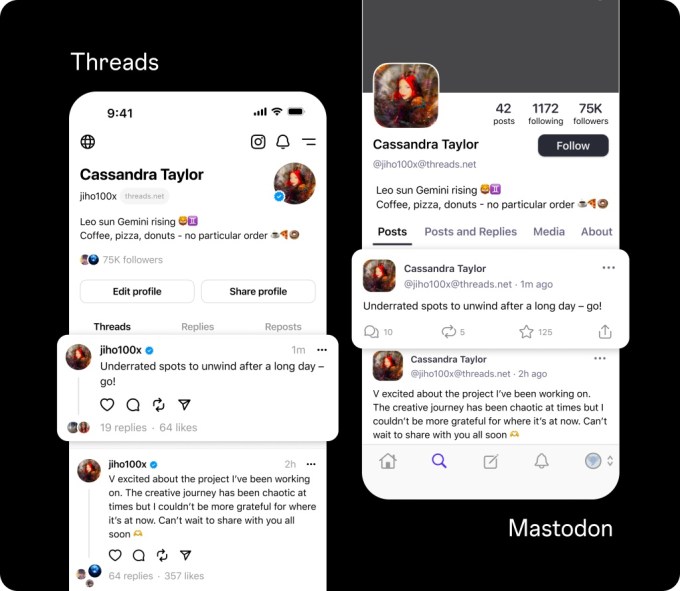

That’s only true to a point, however. While the fediverse is active and growing, Threads is already a dominant app in the space. Outside of Threads’ now 150 million monthly active users, the wider fediverse has just north of 10 million users. Mastodon, a top federated app, has fallen below 1 million monthly active users after Threads launched.

So if Threads joining the fediverse is not about significantly widening creators’ reach, then what is Meta’s aim?

The Meta employees’ remarks hinted at a broader reason behind Meta’s shift to the fediverse.

Bringing the creator economy to the open social web

Image Credits: Meta

Lambert suggests that, by joining the fediverse, creators on Threads have the opportunity to “own their audiences in ways that they aren’t able to own on other apps today.”

But this isn’t only about account portability; it’s also about creators and their revenue streams potentially leaving Meta’s walled garden. If creators wanted to leave Meta for other social apps where they had more direct relationships with fans, there are still few sizable options outside of TikTok and YouTube.

If those creators joined the fediverse — perhaps to get away from Meta’s hold on their livelihoods — Threads users would still benefit from their content. (Cue “Hotel California“).

Later in the podcast, Cottle expands on how this could play out at the protocol level, as well, if creators offered their followers the ability to pay for access to their content.

“You could imagine an extension to the protocol eventually — of saying like, ‘I want to support micropayments,’ or … like, ‘hey, feel free to show me ads, if that supports you.’ Kind of like a way for you to self-label or self-opt-in. That would be great,” Cottle noted, speaking casually. Whether or not Meta would find a way to get a cut of those micropayments, of course, remains to be seen.

McCue riffed on the idea that fediverse users could become creators where some of their content became available to subscribers only, similar to how Patreon works. For instance, fediverse advocate and co-editor of ActivityPub Evan Prodromou created a paid Mastodon account (@evanplus@prodromou.pub) that users could subscribe to for $5 per month to gain access. If he’s on board with paid content, surely others would follow. Cottle agreed that the model could work with the fediverse, too.

He additionally suggested there are ways the fediverse could monetize beyond donations, which is what often powers various efforts today, like Mastodon. Cottle said someone might even make a fediverse experience that consumers would pay for, the way some fediverse client apps are paid today.

“The servers aren’t free to run. And eventually, somebody needs to find a way to … sustain the costs of the business,” he pointed out. Could Meta be pondering a paid federated experience, like Medium launched?

Moderation services at the protocol level

The podcast yielded another possible answer as to what Meta may be working on in the space, with a suggestion that it could bring its moderation expertise to the ActivityPub protocol.

“A lot of the instruments that we have for people to feel safe and to feel like they’re able to personalize their experience are pretty blunt today. So, you can block users … you can do server-level blocking overall, which is a really big action, but you’re kind of missing some other tools in there that are a little bit more like proportional response,” explained Lambert.

Today, fediverse users can’t do things like filter their followers or replies for offensive content or behavior in the same way as they can on Instagram. “That would be great for us to develop as more of a standard at the protocol level,” she added. (Of note, Threads just launched the ability to filter out words, phrases, and emoji and added tools to mute notifications and controls for quote posts.)

Still, Lambert said that whatever work Meta does it wouldn’t expect everyone in the fediverse to adopt its own toolkit.

Image Credits: Automattic

“We’ve built our technology around a set of policies, and our policies are informed by a lot of different inputs from civil rights groups, policy stakeholders, and just the values of our company, generally. So we certainly wouldn’t want to presume that that is now the standard within the fediverse for how to do moderate, but making those tools more available so people have that option seems like a really compelling path from our perspective.”

Meta’s plan also sounds a lot like Bluesky’s idea around stackable moderation services, where third parties can offer moderation services on top of Bluesky either as independent projects from individuals or communities or even as paid subscription products.

Perhaps Meta, too, sees a future where its existing moderation capabilities become a subscription revenue product across the wider open social web.

Finally, Lambert described a fediverse user experience where you could follow the conversations taking place around a post across multiple servers more easily.

“I think that in combination with the tools that allow you to personalize that experience will … help people feel more safe and in control,” she said.