After years of hacking servers to swindle millions of dollars, the notorious Ebury malware gang had slipped into the shadows by 2021. Suddenly, they reemerged with a bang.

The new evidence surfaced during a police investigation in the Netherlands. A cryptocurrency theft had been reported to the Dutch National High Tech Crime Unit (NHTCU). On the victim’s server, the cybercops found a familiar foe: Ebury.

The discovery revealed a new target for the botnet. Ebury had diversified to stealing Bitcoin wallets and credit card details.

The NHTCU sought assistance from ESET, a Slovakian cybersecurity firm. The request reopened a case that Marc-Etienne Léveillé has investigated for over a decade.

Back in 2014, the ESET researcher had co-authored a white paper on the botnet operations. He called Ebury the “most sophisticated Linux backdoor ever seen” by his team.

Cybercriminals use Ebury as a powerful backdoor and credential stealer. After entering a server, the botnet can also deploy further malware, redirect web visitors to fraudulent ads, and run proxy traffic to send spam. According to US officials, the operation fraudulently generated millions of dollars in revenue.

“It’s very well done and they’ve been able to stay under the radar for so many years,” Léveillé tells TNW.

A year after ESET’s original paper was published, an alleged Ebury operator was arrested in Finland. His name was Maxim Senakh. The Finnish authorities then extradited the Russian citizen to the US.

The 41-year-old eventually pleaded guilty to a reduced set of computer fraud charges. In 2017, he was sentenced to nearly four years in prison.

In a press release, the US Justice Department said Ebury had infected “tens of thousands” of servers across the world. Yet that was just a fraction of the total.

Hello ESET honeypot

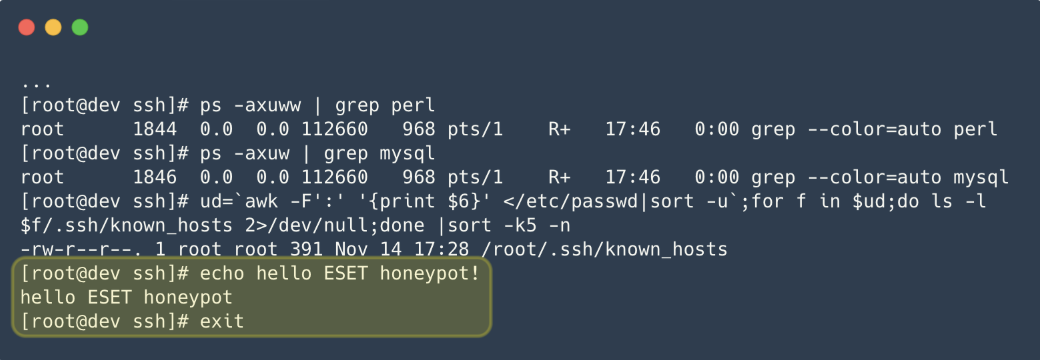

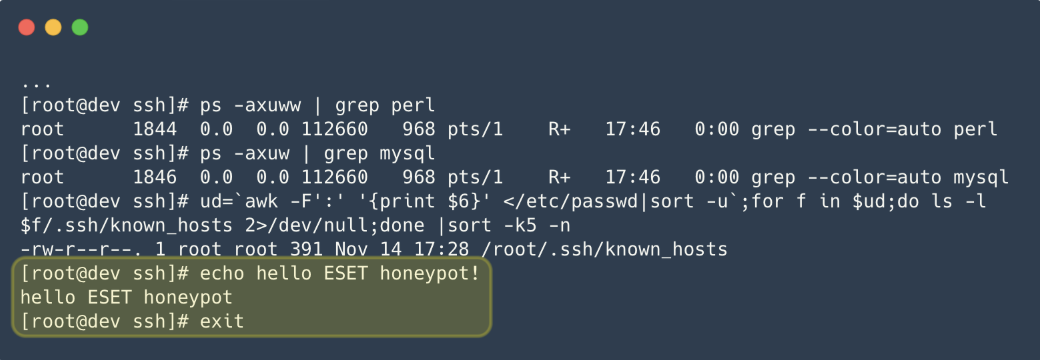

While Senakh’s trial progressed, ESET’s researchers ran honeypots to track Ebury’s next moves. They discovered that the botnet was still expanding and receiving updates. But their detective work didn’t stay concealed for long.

“It was getting more and more difficult to make the honeypots undetectable,” Léveillé says. “They had a lot of techniques to see them.”

One honeypot reacted strangely when Ebury was installed. The botnet’s operators then abandoned the server. They also sent a message to their adversaries:”Hello ESET honeypot!”

As the case went cold, another one was developing in the Netherlands.

By late 2021, the NHTCU had created another lead for ESET. Working together, the cybercrime unit and cybersecurity firm investigated Ebury’s evolution.

“The botnet had grown,” Léveillé says. “There were new victims and even larger incidents.”

ESET now estimates that Ebury has compromised about 400,000 servers since 2009. In a single incident last year, 70,000 servers from one hosting provider were infected by the malware. As of late 2023, over 100,000 servers from one hosting provider were still compromised.

Some of these servers were used for credit card and cryptocurrency heists.

The botnet comes for Bitcoin

To steal cryptocurrency, Ebury deployed adversary-in-the-middle attacks (AitM), a sophisticated phishing technique used to access login credentials and session information.

By applying AitM, the botnet intercepted network traffic from interesting targets inside data centres. The traffic was then redirected to a server that captured the credentials.

The hackers also leveraged servers that Ebury had previously infected. When these servers are in same network segment as the new target, they provide a platform for spoofing.

Among the lucrative targets were Bitcoin and Ethereum nodes. Once the victim entered their password, Ebury automatically stole cryptocurrency wallets hosted on the server.

The AitM attacks provided a powerful new method of quickly monetising the botnet.

“Cryptocurrency theft was not something that we’d ever seen them do before,” Léveillé says.

The Dutch investigation continues

The variety of Ebury victims has also grown. They now span universities, small businesses, large enterprises, and cryptocurrency traders. They also include internet service providers, Tor exit nodes, shared hosting providers, and dedicated server providers.

To conceal their crimes, Ebury operators often use stolen identities to rent server infrastructure and conduct their attacks. These techniques have investigators in the wrong directions.

“They’re really good at blurring the attribution,” Léveillé says.

The NHTCU found further evidence of the obfuscation. In a new ESET white paper, the Dutch crimefighters highlighted several anonymisation techniques.

Ebury’s digital footprints often proved to be faked, the NTCU said. The tracks frequently led to (seemingly) innocent people.

Operators also used the monikers and credentials of known cybercriminals to shake investigators off the trail. On one seized backup server, the NHTCU found a full copy of an illicit website with logins harvested by other crooks.

“Hence the Ebury group does not only benefit from the theft of the already stolen login credentials, but is also in a position to use the credentials of the cybercriminals stealing them,” the Dutch police unit said.

“Consequently, they can create a ‘cybercriminal cover’ pointing in other directions than themselves.”

Despite these red herrings, the NHTCU says “several promising digital identities” are being actively pursued. Léveille, meanwhile, is taking another break from his 10-year investigation.

“It’s not closed, but I’m not sure about any individuals behind it,” he says. “That’s still an unknown — for me at least.”